Geoff Dutton | in

Geoff Dutton | in  Business,

Business,  Design,

Design,  Technology

Technology

Everyone knows that Thomas Edison invented the phonograph. Well, sort of. Actually, he improved a device to record and reproduce sound in 1877 that others (including Alexander Graham Bell) made better. Edison himself drew on an invention called the phonautograph, which recorded sound with a stylus on paper covered with carbon black and wrapped around a cylinder. That device, invented by Eduard-Leon Scott de Martinville 20 years before Edison's, could record sound but not reproduce it. And as innovative as the phonautograph was, it never went to market.

Edison didn't "invent" the light bulb either; he made them last longer, and then started a company to power them. The difference between Edison and many unsuccessful inventors was that he knew how to hunt down cool ideas and technologies, mobilize people to turn them into working, useful products, drum up the public's interest in what he was doing, and then parlay that into new ventures.

So, innovations arise from a confluence of ideas, ambitions, people, and institutions that interact in countless ways over time. They don't just appear in a flash of light. As revolutionary and useful an idea may be, it won't get off the ground if its inventor doesn't cultivate the right sort of people to develop and popularize it.

Innovation tends to follow certain patterns as it evolves from a cool idea into useful products or practices. Management consultant and MIT professor Peter Gloor has mapped out these pathways by studying successful inventions in a number of areas. His most recent book, Coolfarming: Turn Your Great Idea into the Next Big Thing, describes how social networks evolve into organizations to turn a vision into reality. "Coolfarming" is Gloor's label for the collaborative innovation process, which he says generally goes like this:

This scenario is not like the orderly process of project planning which companies typically follow to develop and launch a new product. In particular, it is charismatic, iterative, serendipitous, non-linear, and depends on outside resources at least as much as inside ones.

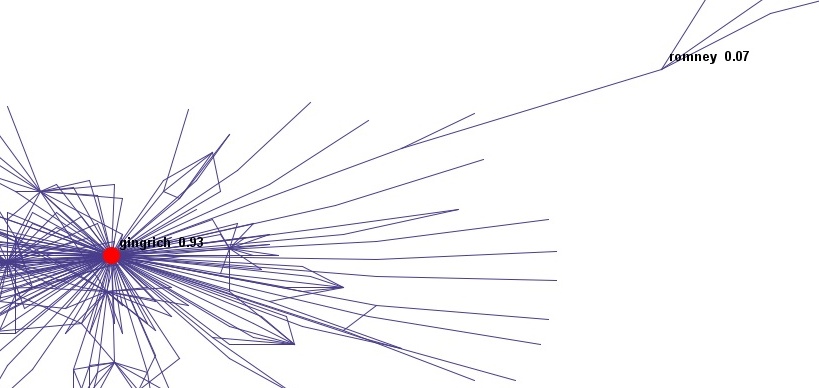

Gloor's cool farm is the Internet, and the crops he harvests consist of buzz (both positive and negative) about certain topics, plus linkages between the principles and other people in emails, online forums and other modes of interaction. His farm machinery is a set of applications that he and his associates coded that search for terms and connections on the Web and in email to compile lists of respondents and links to associated content. The software harvests and processes this data to determine who talks to whom, how frequently, and whether their interactions are positively or negatively reinforcing. The results display as spider-web graphs connecting clusters of individuals that morph into more extensive networks or atrophy (see example below).

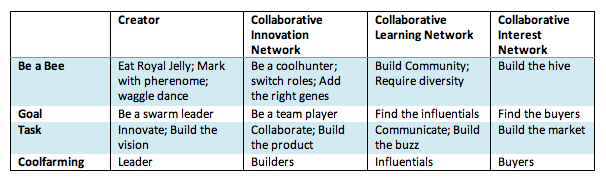

Edison's Laboratory in Menlo Park, New Jersey was a beehive of activity. Throughout his book, Gloor frequently compares innovators to a hive of bees, not because bees create buzz, but because they exhibit "swarm creativity." In a hive, bees have specific roles, which can change over time. Worker bees search their territory for food, and when they find some, communicate its location by "dancing." The more intense the dance, the more likely other bees will take notice and fly to investigate. Gloor likens entrepreneurs to queen bees, and interactions among bees to communications between people who form collaborative networks for innovating, learning, and building interest in their work. Coolfarming summarizes the innovation process and the beehive analogy like this:

Gloor deconstructs the process of innovation by peering into social network activity. His Web tools monitor chatter about political issues and associated memes, enabling predictions of how they might trend. For example, he analyzed discussions to predict whether the Eurozone will break up or stay together (and found pretty even chances so far). Here's a different example of the same tooling, a diagram showing tweets in Florida mentioning Mitt Romney and Newt Gingrich a week before the primary that Gingrich decisively won. Assuming this visualization accurately represents that tweetscape, it does seem to be a good predictor of the primary's outcome.

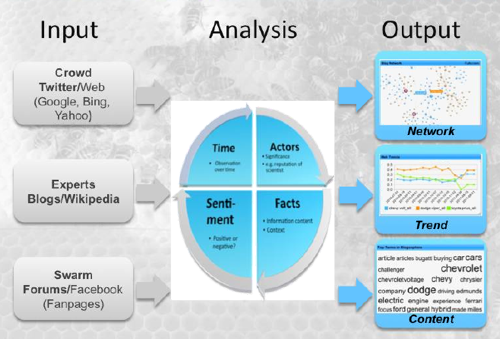

Gloor calls his process of analyzing interactions to predict trends coolhunting, and with Scott Cooper published a book about it five years ago. Here is how his software coolhunts (taken from a slide talk).

The ease and speed with which Gloor's analytic methods can harvest and interpret data from the Internet -- essentially in real time -- is astonishing. With such tools, corporations, governments and political parties will soon be able to anticipate our every move. I'm not sure how I feel about that.

Read other posts in Gloor's blog to see examples of how he mines the Web to sniff out trends and predicts their fates. You need to know, because your online breadcrumbs are already being harvested by coolhunters and used by coolfarmers to make honey, i.e., money. Isn't it time they shared that sweetness with us worker bees?

By Geoff Dutton

Reader Comments