Tuesday, April 24, 2012 at 11:43AM |

Tuesday, April 24, 2012 at 11:43AM |  1 Comment

1 Comment Geoff Dutton | in

Geoff Dutton | in  Consumer Power,

Consumer Power,  Food,

Food,  Well-Being

Well-Being

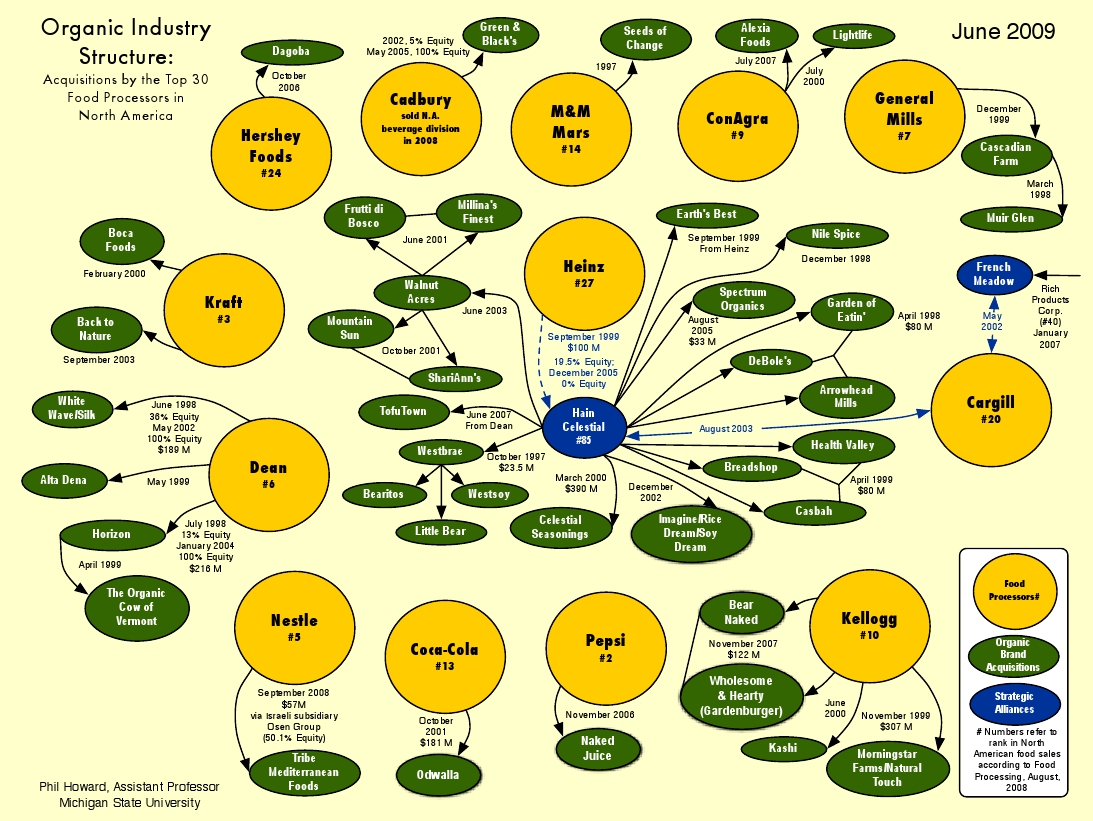

Across the world, organic (variously called bio, eco or oko) food's cultural cachet and steadily rising market share has caused policy makers to regulate how it is produced and marketed. As the illustration below makes clear, its production has become "vertically integrated," making it harder for consumers to decode and trust than ever. Food bureaucracies are also complicating organic farmers' lives.

Suppose you're a small U.S. farmer who wants to grow healthier food without using chemical pesticides and fertilizers. Of course, you want your produce, livestock, eggs, and/or dairy products to be officially certified as "organic." And if you produce processed foods, you need to know what additives you can safely use. With the help of trade organizations, you start collecting information about how to follow best practices and satisfy "applicable regulations." Eventually, you note that the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) runs something called the National Organic Program (NOP) that's in charge of regulating organic food production.

So you search for its Web site and go there to look around. There you find the fruit of an entrenched bureaucracy trying to come to grips with a new environmental and consumer ethic, which will keep you up at night for some time to come.

(Illustration by Philip H. Howard. View larger.)

(Illustration by Philip H. Howard. View larger.)

The NOP was established under a 1990 law, the Organic Foods Production Act, but did not formulate any regulations until 1998. It is part of the USDA Agricultural Marketing Service, which is huge, with a $1.3B budget and 2600 employees. AMS promotes American agricultural products, and runs commodity programs for dairy, fruit and vegetable, livestock and seed, poultry, and cotton and tobacco. It does testing, standardization, grading, and oversees marketing. The NOP is one of its lesser activities, and sometimes conflicts with its other goals, such as its agribusiness subsidy programs.

NOP regulations cover every aspect of agricultural practice, from soil preparation to labeling. They took eight years to codify and 12 years to release, due to concerted conniving from the "conventional food" industry and pushback from the organic side. The definition of "organic" that emerged is spelled out in section 205.102:

A raw or processed agricultural product sold, labeled, or represented as 'organic' must contain (by weight or fluid volume, excluding water and salt) not less than 95 percent organically produced raw or processed agricultural products. Any remaining product ingredients must be organically produced, unless not commercially available in organic form, or must be nonagricultural substances or nonorganically produced agricultural products produced consistent with the National List.

The regulations elaborate on what this entails for producers and consumers in a mere 30,000 words. Couldn't be clearer.

Objections came from many quarters to V 1.0 of the USDA regulations for organic food production. Food activists argued that the proposed rules would allow genetically engineered crops and organisms in organic agriculture, permit irradiation of organically produced food, allow municipal sewage sludge to be applied as fertilizer, and not encourage biodiversity. Fortunately, USDA took their concerns seriously and overruled these provisions.

The job of defining what's organic and what isn't falls to the NOP's 15-member National Organic Standards Board (NOSB), composed of four farmers/growers, three environmentalists/resource conservationists, three consumer/public interest advocates, two handlers/processors, a retailer, a scientist, and a USDA-accredited certifying agent. That's a decent mix, but 15 people can't hope to handle all the concerns that organic producers and consumers bring to them, which are many.

By far, the most important thing that the NOSB does is to maintain the National List of Allowed and Prohibited Substances (called the National List) that identifies substances and methods that may and may not be used in organic crop and livestock production. The NOSB fiddles with these rules at every biannual meeting. NOP regulations categorize organic food ingredients and inputs as follows:

§ 205.601 Synthetic substances allowed for use in organic crop production

§ 205.602 Nonsynthetic substances prohibited for use in organic crop production

§ 205.603 Synthetic substances allowed for use in organic livestock production

§ 205.604 Nonsynthetic substances prohibited for use in organic livestock production

§ 205.605 Nonagricultural (nonorganic) substances allowed as ingredients in or on processed products labeled as “organic” or “made with organic (specified ingredients or food group(s))”

§ 205.606 Nonorganically produced agricultural products allowed as ingredients in or on processed products labeled as “organic”

The National List allows many more ingredients to be in organic foods than it explicitly prohibits. Click any of the above six links to see what they are. (Can ingredients that are not mentioned be used?) This article summarizes objections from organic food advocates to some ingredients USDA decided to allow.

The NOP defines the terms synthetic and nonsynthetic. Synthetic ingredients are "naturally occurring plant, animal, or mineral sources" that are chemically processed. Nonsynthetic ones come from like sources but must remain unaltered, except by "naturally occurring biological processes," presumably such as fermentation or drying.

And in case you have wondered what "all natural" means, all the regs say is "nonsynthetic is used as a synonym for natural as the term is used in the Act." Got that?

Bookmark this link to the official National List so that the next time you want to know whether a food promoted as "organic" meets NOSB standards you can check its ingredients. And pity the poor farmer, rancher, baker or canner who has to understand and abide by all of this to certify his or her operation. Going back to the land ain't what it used to be.

If you want to complain to USDA about products you suspect are not really organic, go to this Web page, which gives you guidance and an email address for submitting your comments.

Read an informed international summary of organic food and production methods from ifst.org. Finally, if you can't get enough of this stuff, compare and contrast the European Union's organic food regulations (23 p. PDF) with those above.

By Geoff Dutton

Top photo by Tim Psych

Tuesday, April 24, 2012 at 11:43AM |

Tuesday, April 24, 2012 at 11:43AM |  1 Comment

1 Comment Geoff Dutton | in

Geoff Dutton | in  Consumer Power,

Consumer Power,  Food,

Food,  Well-Being

Well-Being

The thesis of this article seems to be that: "regulation of Organic agriculture is difficult and complex, and I don't understand it completely, therefore I don't trust it." Criticisms like this have become fashionable lately, but they are- like this one- largely full of innuendo and free from actual logical criticism.

I get it. It's frustrating to read language you don't understand. It's sometimes intimidating to read definitions like the one of "natural" you quoted. It seems like legalese, and that seems suspicious to you.

But the thing is, that's the way regulation works! It has to be very specific, very "letter of the law", because, ummm, it IS the law! One of the coolest things about the National Organic Program is that it actually defines, inspects, and enforces what can be and what cannot be called organic. The fact is, you don't need to do the ingredient-inspection you describe to know whether a food follows the organic code: if it carries the USDA's NOP seal, then you know it has been inspected by a NOP accredited certifier (the name of the certifier will be on the package- that's in the law). It's a very transparent and traceable system: the rules are all on the internet, the information is on the label- It's a good system!

I've been working with organic farmers for over a decade, and it's true that a few feel like the NOP code is too complex for them to understand. In my experience, however, organic inspectors are totally willing and encouraged to help small farmers figure out and comply with the code. The code is there to help protect them and consumers from those- including larger corporations who seek to get involved in the organic marketplace- and ensure that everyone is following the same rules. And the NOP is really effective at doing just that. Is the system free from problems? Of course not. That's why it adapts every year, just like all good laws do in a democratic republic.

I can't really tell if the author is pro- or anti-organic, or is just lashing out against regulation. It's pretty easy to be cynical ("getting back to the land ain't what it used to be" har har har) but it's harder to build a system that effectively watches over an agricultural system. I'm grateful to the farmers, food activists, inspectors, and consumers who have built the National Organic System.

Peter Giuliano